In this article, we consider a group \(G\) and two subgroups \(H\) and \(K\). Let \(HK=\{hk \text{ | } h \in H, k \in K\}\).

\(HK\) is a subgroup of \(G\) if and only if \(HK=KH\). For the proof we first notice that if \(HK\) is a subgroup of \(G\) then it’s closed under inverses so \(HK = (HK)^{-1} = K^{-1}H^{-1} = KH\). Conversely if \(HK = KH\) then take \(hk\), \(h^\prime k^\prime \in HK\). Then \((hk)(h^\prime k^\prime)^{-1} = hk(k^\prime)^{-1}(h^\prime)^{-1}\). Since \(HK = KH\) we can rewrite \(k(k^\prime)^{-1}(h^\prime)^{-1}\) as \(h^{\prime \prime}k^{\prime \prime}\) for some new \(h^{\prime \prime} \in H\), \(k^{\prime \prime} \in K\). So \((hk)(h^\prime k^\prime)^{-1}=hh^{\prime \prime}k^{\prime \prime}\) which is in \(HK\). This verifies that \(HK\) is a subgroup.

Also, if either \(H\) or \(K\) is a normal subgroup of \(G\), \(HK\) is a subgroup of \(G\). This is true as if \(H\) is normal in \(G\) then we get that \(Hk = kk^{-1}Hk = kH\) for every \(k \in K\). Hence \(HK = KH\) so it is a subgroup according to point above.

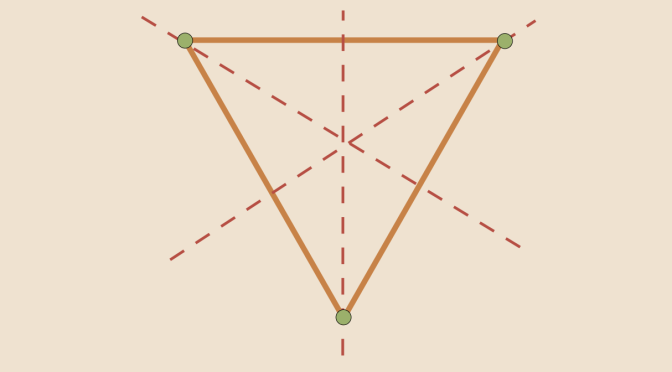

We now move to a counterexample of two subgroups whose product is not a subgroup. For \(G\) we take the dihedral group \(D_3\), the group of symmetries of an equilateral triangle. \(D_3 = \{i, r_1,r_2,s_1,s_2,s_3\}\), here \(i\) is the identity, \(r_1,r_2\) the rotations at \(120\) and \(240\) degrees about the centroid, \(s_1, s_2, s_3\) the axial symmetries with respect to medians. \(H=\{i,s_1\}\) and \(K=\{i,s_2\}\) are two subgroups of \(G\) both of order \(2\). Since the product of reflections (with intersecting axes) is a rotation, \(HK\) will contain \(i\), \(s_1\), \(s_2\) and a rotation. Therefore \(HK\) has 4 distinct elements. \(HK\) cannot be a subgroup as according to Lagrange’s theorem the order of a subgroup divides the order of the group.