In this post, I mention that Peano existence theorem is valid for finite dimensional vector spaces, but not for Banach spaces of infinite dimension. I highlight here a second property of ordinary differential equations which is valid for finite dimensional vector spaces but not for infinite dimensional Banach spaces.

We consider a Banach space \(E\), a real interval \(I\) with \(t_0\) as right endpoint and a function \(\textbf{f}\) defined on \(I \times E\) with codomain \(E\) having following properties:

- \(\textbf{f}\) is continuous.

- \(\textbf{f}\) is locally Lipschitz continuous which means that for every point \((t,\textbf{x}) \in I \times E\) we can find a neighborhood \(V\) of \(t\), a neighborhood \(W\) of \(\textbf{x}\) and a number \(k>0\) such that \(\Vert \textbf{f}(s,\textbf{x}_1)-\textbf{f}(s,\textbf{x}_2) \Vert \le k \Vert \textbf{x}_1 – \textbf{x}_2 \Vert\) for all \(s \in V\) and all \(\textbf{x}_1,\textbf{x}_2 \in W\).

With above conditions met and according to the Picard–Lindelöf theorem, the differential equation \(\textbf{x}^\prime = \textbf{f}(t,\textbf{x})\) is having a unique maximal solution \(\textbf{u}\) to the initial value problem \(\textbf{x}(t)=\textbf{x}_0\) defined on an interval \(J \subseteq I\).

If \(J \neq I\) and \(E\) of finite dimension, one can prove that \(\lim\limits_{t \rightarrow a^+} \textbf{u}(t) = + \infty\) where \(a\) is \(J\) lower endpoint. This might not be the case when \(E\) if of infinite dimension. Following counterexample is from the French mathematician Jean Dieudonné.

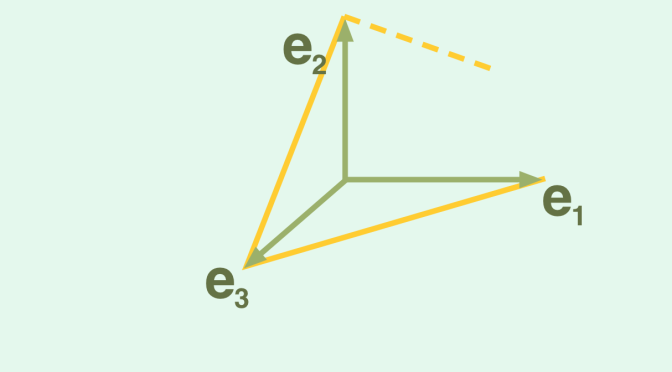

We pick up for \(E\) the Banach space of real sequences converging to \(0\) for the norm \(\Vert \textbf{x} \Vert = \sup_n \vert x_n \vert\) and define as \(\textbf{e}_n\) the sequence whose terms are all vanishing except the one of index \(n\) whose value is equal to \(1\). For all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), we define the map from \(E\) to \(E\):

\[\textbf{f}_n(\textbf{x})=[2(x_n+x_{n+1})-1]^+(\textbf{e}_{n+1}-\textbf{e}_{n})\] with \(\textbf{x}=(x_m) \in E\).

\(\textbf{f}_n\) is lipschitz continuous, vanishes on the closed ball \(\Vert \textbf{x} \Vert \le \frac{1}{4}\) and \(\textbf{f}_n(\textbf{x})=\textbf{e}_{n+1}-\textbf{e}_n\) for \(\textbf{x}=\lambda \textbf{e}_n + (1-\lambda) \textbf{e}_{n+1}\) where \(\lambda\) is any real. For all integers \(n > 0\), we pick up a continuous positive map \(\varphi_n\) defined on the interval \([\frac{1}{n+1},\frac{1}{n}]\), vanishing at the endpoints of this interval and such that \(\displaystyle \int_{\frac{1}{n+1}}^{\frac{1}{n}} \varphi_n(t) dt=1\).

Let \(I=(-\infty,1]\) and define the map:

\[\begin{array}{l|rcl}

\textbf{f} : & I \times E & \longrightarrow & E\\

& (t,\textbf{x}) & \longmapsto & \textbf{0} \text{ for } t \le 0\\

& (t,\textbf{x}) & \longmapsto & \varphi_n(t)\textbf{f}_n(\textbf{x}) \text{ for } t \in [\frac{1}{n+1},\frac{1}{n}]\end{array}\]

It is clear that \(\textbf{f}\) is continuous and locally Lipschitz continuous at all points \((t_0,\textbf{x}_0) \in I \times E\) for \(t_0 \neq 0\). We prove that the assertion is also true at all points \((0,\textbf{a})\) with \(\textbf{a}=(a_n)\). Because \(\textbf{a}\) converges to zero, one can find \(m \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(\vert a_n \vert \le \frac{1}{8}\) for \(n \ge m\). Hence for \(\textbf{x} \in E\) and \(\Vert \textbf{x} – \textbf{a} \Vert \le \frac{1}{8}\) we get \(\vert x_n \vert \le \frac{1}{4}\) for \(n \ge m\) and therefore \(\textbf{f}_n(\textbf{x})=\textbf{0}\) for all \(n \ge m\). Finally, \(\textbf{f}(t,\textbf{x})\) vanishes for \(t \in [0,\frac{1}{m}]\) and \(\Vert \textbf{x} – \textbf{a} \Vert \le \frac{1}{8}\) leading to the expected conclusion.

We now define a sequence (for \(n \ge 1\)) of maps \(\textbf{v}_n: I\ \mapsto E\):

\[\textbf{v}_1(t) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{ for } t < \frac{1}{2}\\

\textbf{e}_1+(\textbf{e}_2-\textbf{e}_1) \int_t^1 \varphi_1(s) ds & \text{ for } \frac{1}{2} \le t \le 1 \end{cases}\] and for \(n \ge 2\):

\[\textbf{v}_n(t) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{ for } t < \frac{1}{n+1} \text{ or } t > \frac{1}{n}\\

(\textbf{e}_{n+1}-\textbf{e}_n) \int_t^{\frac{1}{n}} \varphi_n(s) ds & \text{ for } \frac{1}{n+1} \le t \le \frac{1}{n} \end{cases}\] For \(0 < t \le 1\), the series \(\textbf{u}(t) = \displaystyle \sum_{n=1}^\infty \textbf{v}_n(t)\) is eventually vanishing and therefore well defined. For \(\frac{1}{n+1} \le t \le \frac{1}{n}\) we have \(\textbf{u}(t)=\textbf{e}_n+(\textbf{e}_{n+1}-\textbf{e}_n) \int_t^{\frac{1}{n}} \varphi_n(s) ds\) which implies that \(\Vert \textbf{u}(t) \Vert \le 1\) for \(0 < t \le 1\), and is differentiable in this interval. Considering the definition of \(\textbf{f}\) we get \(\textbf{u}^\prime(t)=-\textbf{f}(t,\textbf{u}(t))\). We also notice that \(\textbf{u}(1/n)=\textbf{e}_n\) for all positive integers. Hence, \(\textbf{u}(t)\) has no limit when \(t\) tends to \(0\). Consequently \(\textbf{u}\) is a solution of the initial value problem \(\textbf{x}^\prime(t)=-\textbf{f}(t,\textbf{x}(t))\) and \(\textbf{x}(1)=\textbf{e}_1\). \(J=(0,1]\) is the maximal interval of the solution \(\textbf{u}\).

We have proven that \(J \neq I\) while \(\textbf{u}(t)\) remains bounded on \(J\) as desired.

Dear Jean-Pierre Merx,

Thanks for another enlightening example! 🙂

I think there is a typo in the definition of $v_n$ for $n \ge 2$: instead of $\varphi_1$ shouldn’t be $\varphi_n$?

Thanks and best regards!

Dear Tadashi,

Thank you for your attentive reading. You’re absolutely right. And I made the relevant modification.$

Best regards, Jean-Pierre.