Recall that a topological space is considered separable when it contains a countable dense set. The following theorem establishes a significant connection between separability and dual spaces:

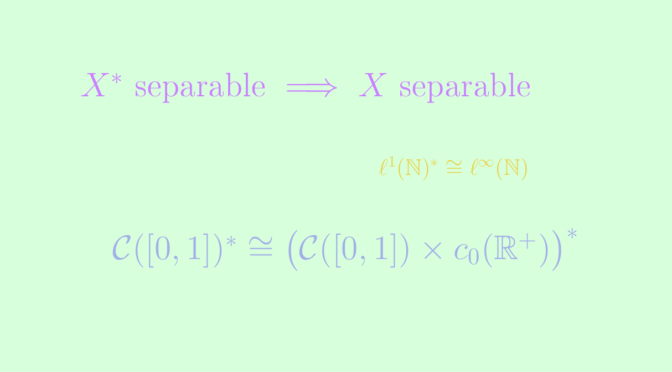

Theorem: If the dual \(X^*\) of a normed vector space \(X\) is separable, then so is the space \(X\) itself.

Proof outline: let \({f_n}\) be a countable dense set in \(X^*\) unit sphere \(S_*\). For any \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) one can find \(x_n\) in \(X\) unit ball such that \(f_n(x_n) \ge \frac{1}{2}\). We claim that the countable set \(F = \mathrm{Span}_{\mathbb{Q}}(x_0,x_1,…)\) is dense in \(X\). If not, we would find \(x \in X \setminus \overline{F}\) and according to the Hahn-Banach theorem, there would exist a linear functional \(f \in X^*\) such that \(f_{\overline{F}} = 0\) and \(\Vert f \Vert=1\). But then for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), \(\Vert f_n-f \Vert \ge \vert f_n(x_n)-f(x_n)\vert = \vert f_n(x_n) \vert \ge \frac{1}{2}\). A contradiction since \({f_n}\) is supposed to be dense in \(S_*\).

We prove that the converse is not true, i.e., a dual space can be separable, while the space itself may not be.

Introducing some normed vector spaces

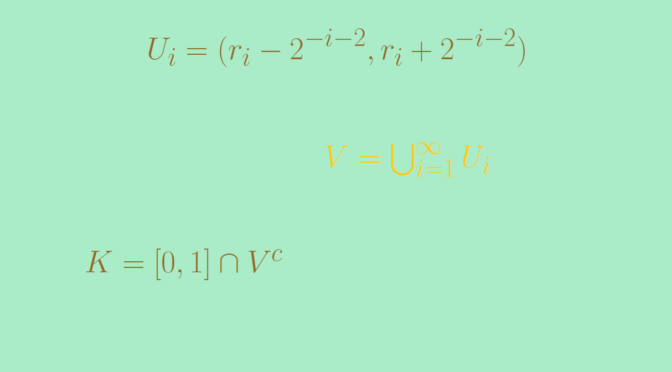

Given a closed interval \(K \subset \mathbb{R}\) and a set \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\), we define the \(4\) following spaces. The first three are endowed with the supremum norm and the last with the \(\ell^1\) norm.

- \(\mathcal{C}(K,\mathbb{R})\), the space of continuous functions from \(K\) to \(\mathbb{R}\), is separable as the polynomial functions with coefficients in \(\mathbb{Q}\) are dense and countable.

- \(\ell^{\infty}(A, \mathbb{R})\) is the space of real bounded functions defined on \(A\) with countable support.

- \(c_0(A, \mathbb{R}) \subset \ell^{\infty}(A, \mathbb{R})\) is the subspace of elements of \(\ell^{\infty}(A)\) going to \(0\) at \(\infty\).

- \(\ell^1(A, \mathbb{R})\) is the space of summable functions on \(A\): \(u \in \mathbb{R}^{A}\) is in \(\ell^1(A, \mathbb{R})\) iff \(\sum \limits_{a \in A} |u_x| < +\infty\).

We find the usual sequence spaces when \(A = \mathbb{N}\). It should be noted that \(c_0(A, \mathbb{R})\) and \(\ell^1(A, \mathbb{R})\) are separable iff \(A\) is countable (otherwise the subset \(\big\{x \mapsto 1_{\{a\}}(x),\ a \in A \big\}\) is uncountable, and discrete), and that \(\ell^{\infty}(A, \mathbb{R})\) is separable iff \(A\) is finite (otherwise the subset \(\{0,1\}^A\) is uncountable, and discrete).

Continue reading Separability of a vector space and its dual